February is Black History Month. And what better way to celebrate than to lift from obscurity African Americans who played crucial roles in this country’s scientific, cultural and industrial progress. Their achievements saved thousands of lives, made the lives of many Americans easier and in some instances changed the course of history. And yet, they are largely forgotten by the world they helped to change for the better. In this series, we will highlight some of these under-appreciated and forgotten men and women.

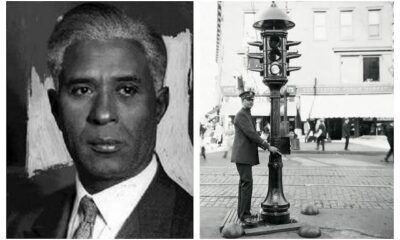

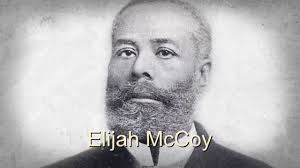

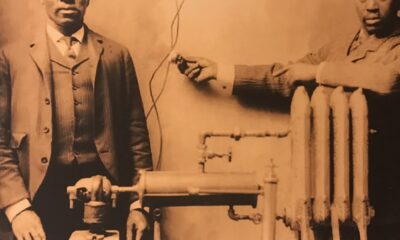

Most people may not know his name, but many know the phrase: it’s the real McCoy. That’s because the quality of Elijah McCoy’s inventions created a level of distinction that continues to bear his name.

McCoy was born on May 2, 1844 in Colchester, Ontario in Canada to slaves who escaped from Kentucky through the underground railroad (the movement began by abolitionists and others to help move escaped slaves from the South into Canada).

Some years later, the family moved back to the United States and settled in Ypsilanti, Michigan where McCoy attended grammar school. Young McCoy was always tinkering with any machine he could lay his hands on, often taking them apart and putting them back together again. Seeing his aptitude, His parents arranged for the then 15-year-old to travel to Edinburgh, Scotland to work as an apprentice in mechanical engineering, according to Biography.com.

He later returned to Michigan as a certified mechanical engineer. But no company wanted to hire a black man, especially to such a highly-skilled position.

“Skilled professional positions were not available for African Americans at the time, regardless of their training or background,” according to Biography.com. Instead, he became a fireman and oiler on the Michigan Central Railroad.

As a fireman, McCoy shoveled coal onto fires which would help to produce steam that powered the locomotive. As an oilman, he was responsible for ensuring that the train was well lubricated.

At that time, the trains had to be stopped every few miles and an oilman would go around oiling the engine, wheels and other moving parts, according to Louis Haber, author of Black Pioneers of Science and Invention. That method was repeated in factories where the machines would have to be shut down in order to be oiled or lubricated to prevent friction or burn out from the parts coming together.

McCoy thought frequently shutting down the machines was a waste of time and money. He built a crude machine shop and there worked on developing a way to lubricate the machines while they were in operation.

“His idea was to provide, in the making of the machine, for certain canals with connecting devices to distribute the oil throughout the machinery and whenever needed, rather than have to figure out the need from memory – in other words, to make lubrication automatic,” Haber said. “He called his device the ‘lubricating cup.’”

In July, 1872, McCoy patented his first invention of an automatic lubricator that distributed oil evenly over the engine’s moving parts, particularly for steam engine and steam cylinder. The lubricating cup allowed trains to run continuously for long periods of time without pausing for maintenance. A year later, he improved on his invention of a steam cylinder lubricator by providing additional devices so that the lubricator mainly oiled when the steam was exhausted, which was when the oil was needed the most, Haber said.

Factories everywhere were quick to adopt McCoy’s lubricating cups.

By 1892, McCoy had moved on to solving the problem of lubricating railroad locomotives. He was able to establish a perfect equalization of the steam pressure going in and out of the engine, resulting in proper lubrication, Haber said.

His system was soon be used on all railroads in the West and on steamers on the Great Lakes, Haber said. In 1920, McCoy applied his lubrication system to the air brakes on locomotives and other vehicles that used air brakes.

Although McCoy’s achievements were recognized in his own time, his name did not appear on the majority of the products that he devised, according to Biography.com.

He didn’t have the capital needed to manufacture his lubricators in large numbers, so he typically assigned his patent rights to his employers or sold them to investors, according to the online site. But that soon changed.

In 1916, McCoy created the graphite lubricator that oiled new superheater trains and devices, according to Blackinventor.com. Four years later he started the Elijah McCoy Manufacturing Company where he improved and sold the graphite lubricator as well as other inventions, which came to him out of necessity. He developed and patented a portable ironing board after his wife, Mary Eleanor Delaney, expressed a need for an easier way of ironing clothes. When he desired an easier and faster way of watering his lawn, he created and patented the lawn sprinkler, according to the online site.

Over the years, McCoy received 57 patents, most of which were in the field of automatic lubrication. His lubrication systems came into general use on industrial and locomotive machinery throughout the United States and elsewhere in the world. After a while, no piece of heavy-duty equipment was considered complete unless it had the “McCoy system.”

In 1922, Elijah and his wife got into an automobile accident. His wife died, while McCoy was critical injured and developed heart problems, according to Blackinventor.com. He never really recovered and died in the Eloise Infirmary in Detroit on Oct.10, 1929. He was 85.

Over the years, other inventors attempted to sell their own versions of his invention, the lubricating cup, but most companies wanted the authentic device, requesting “the Real McCoy.”

“People inspecting a new machinery would make sure that it had automatic lubrication by asking, “Is it the real McCoy?” Haber said. Today the expression, “It’s the real McCoy,” is used to indicate perfection, he said.

Black History5 years ago

Black History5 years ago

Black History6 years ago

Black History6 years ago

Black History4 years ago

Black History4 years ago

Black History5 years ago

Black History5 years ago

Black History5 years ago

Black History5 years ago

Black History9 years ago

Black History9 years ago

Black History5 years ago

Black History5 years ago

Black History6 years ago

Black History6 years ago