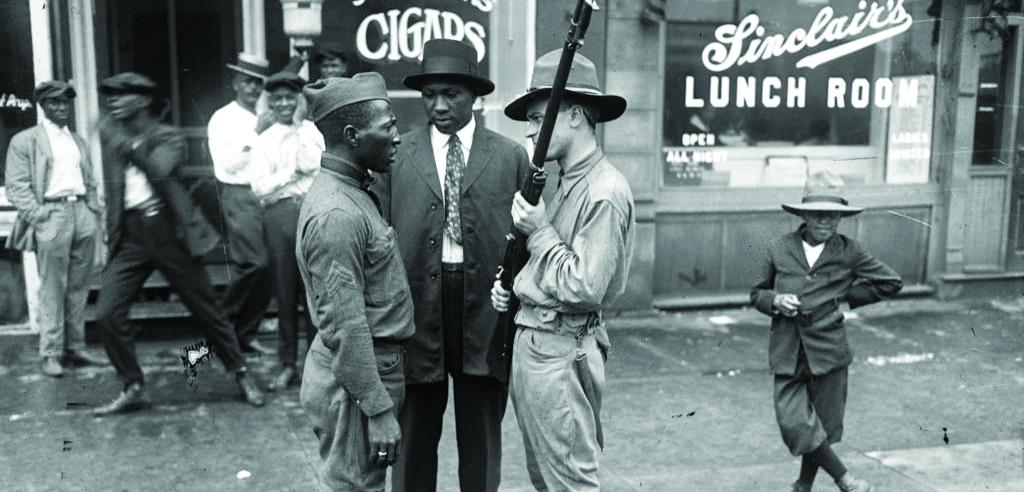

The summer of 1919 was an extraordinarily bloody period of racial violence in American history, so much so that black author and activist, James Weldon Johnson referred to the era as the “Red Summer.” The tensions spawned race riots and lynchings throughout the summer and early fall in over 30 American cities.

These incidents not only occurred in the segregated South but in northern cities such as Chicago, Philadelphia, and New York City. Large numbers of blacks were attacked all over the country; however, the largest number of blacks were killed in the Elaine race riots in Elaine, Arkansas. It has been estimated that over 250 people were killed before order was reestablished.

Historians attribute the red summer to several factors including post World War I social tensions and competition for jobs and housing among both black and white veterans returning from Europe.

Social tensions arose in America as returning black veterans wanted to maintain the level of freedom they experienced in Europe. The Chicago Daily News reported one returning black veteran said, “[We are] now men and world men, if you please; and the possibilities for completion of what we have awakened to.” Black veterans’ eyes were opened to the possibility of full citizenship.

Upon returning to America, some black veterans resisted the social norms of America. They wanted to hold on to the freedoms they experienced in Europe, the freedoms they felt they earned by fighting in the war. This new sense of manhood directly conflicted with the way of life in America. That conflict precipitated the Red Summer.

One of the lesser known disturbances of that summer occurred in a small southeastern Arkansas town called Star City. Star City is in Lincoln County, about 25 miles from Pine Bluff, Arkansas. Clinton Briggs, the son of Sandy and Catherine Briggs, was born in 1892. In 1917, he registered for the draft and served in Europe until he was discharged a year later. Briggs served honorably during his tenure. He was awarded the Victory Medal and the Victory Lapel Button. He returned to Star City in December of 1918.

Clinton Briggs was lynched on September 1, 1919 in Star City, after allegedly insulting a white woman. The Arkansas Gazette reported that Briggs made “an insulting proposal to the daughter of J.M. Bailey.” Additional accounts indicated that Briggs simply made a statement that a white couple found offensive. Whichever account is true represented a clear violation of Southern social norms, and Briggs was lynched for that violation.

According to reports, Briggs was walking on a sidewalk in town, when a white couple approached. Briggs stepped aside to allow the couple to pass. As they passed, the white woman brushed his shoulder and said, “Niggers get off of the sidewalk down here.” Briggs replied that it was a free country. The white man in the couple grabbed him and a struggle ensued. White passersby surrounded Briggs and he was thrown into a passing car. Briggs was driven three miles outside of town and tied him to a tree with chains. The men then fired as many as fifty bullets into his body, killing him. Briggs’ body was found several days later by a local black farmer.

Clinton Briggs was not an isolated incident. Black veterans were often the target of mob violence and discrimination. Robert Thomas Kerlin noted in 1920 that even the American Legion was segregated, the all-white organization allowed sub-posts to be organized in each county for black veterans under the authority of the local white post. The Hot Springs Echo noted that color didn’t matter when soldiers were in war, but the valor that black soldiers displayed in combat earned them the “double cross” when they returned home.

Briggs’ lynching was not an isolated incident. Frank Livingston was burned alive in El Dorado, Arkansas on May 21, 1919 for allegedly killing the white couple for whom he worked. There are even accounts of black veterans being lynched in their military uniforms. Historian Nan Elizabeth Woodruff has written that soldiers who returned to the South following World War I soon realized that their service was a threat to the traditional, segregated, southern way of life. They soon became targets of local whites who required the black veteran to return to their subordinate way of life. When the veteran did not follow Southern traditions, lynchings took place.

This Memorial Day, let us not only honor the black soldiers who have died in the service of this country since the Revolutionary War, but let us also honor those veterans who survived the horrors of war, to return home and be lynched because they refused to live as less than a man.

Brian Rodgers is a historian who works for the Mosaic Templars Cultural Center in Little Rock. He is also a published author.

Black History5 years ago

Black History5 years ago

Black History6 years ago

Black History6 years ago

Black History4 years ago

Black History4 years ago

Black History5 years ago

Black History5 years ago

Black History5 years ago

Black History5 years ago

Black History6 years ago

Black History6 years ago

Black History9 years ago

Black History9 years ago

Black History5 years ago

Black History5 years ago