It was described

as an area overrun with natural resources. Pine trees covered the north end while

various plants and animals occupied the rest. Birds flocked to Mill Creek,

which was overrun by marine life and at the bottom of the Chesapeake Bay, lay a

bed of oysters – an important food source for the Native Americans who valued

the area as an important hunting and fishing camp.

But little remains

of this area which was in Hampton, Virginia. And centuries later, it is being

remembered for something else – the landing ground for the first Africans.

Their arrival in

1619 at Point Comfort in Virginia changed the course of America’s history. This

month many are commemorating their arrival, and how the knowledge they brought

and skills they invested rescued the dying colony. In the end, not only did

they endure, they thrived. They and their descendants built this nation,

according to historians. And transformed it.

“They didn’t just survive, they created new

music, new art forms,” said Terry Brown, Superintendent, Fort

Monroe National Monument, National Park Service, in Virginia. “They

reclaimed their heritage. They created vibrant responses to American democracy.

It’s one of the greatest survival stories in American history. We created new

families, new traditions. Our contribution is beyond measure.”

Last year, the

400 Years of African-American History Commission was established to create

events that would highlight those contributions. But with no funding from Congress,

the commission has done little.

Brown, who is a

member of the Commission, realized he had to do something, especially with Port

Monroe, formerly Point Comfort, playing such a pivotal role.

He said, “This is

the state where they landed. People started calling, asking me, ‘are you doing

anything?’”

He joined forces

with the National Park Service, the Fort Monroe Authority and the city of

Hampton to create a grand commemoration spread over two days. Now, he can tell

those who call, they are doing a lot.

He tells them

about the walking tour and the campfire talk centered around African American

history. They will see the marker where the 20 and odd landed, the Contraband

Bridge where they were enslaved and freed centuries later. General Benjamin

Butler’s “Contraband Decision” in 1861 provided a route to freedom for

thousands of slaves during the Civil War. It was the forerunner for President

Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation of 1863.

President Barack Obama’s Proclamation

“Old Point

Comfort marks both the beginning and end of slavery in our Nation,” then-

President Barack Obama said in his proclamation of the Fort Monroe National Monument

on Nov. 1. 2011.

“Known first as

“The Gibraltar of the Chesapeake” and later as “Freedom Fortress,” Fort Monroe

on Old Point Comfort in Virginia has a storied history in the defense of our

Nation and the struggle for freedom.”

In his statement

he debunked the myth that had been taught for generations, that the first

Africans landed in Jamestown.

“The first

enslaved Africans in England’s colonies in America were brought to this

peninsula on a ship flying the Dutch flag in 1619,” Obama said. “Two hundred

and forty-two years later, Fort Monroe became a place of refuge for those later

generations escaping enslavement.”

Still, many

aren’t aware of this history. And for them, this month will come and go like

any other. Brown and others are trying to change that.

“The nation

doesn’t even know its 400 years,” Brown said. “It’s breaking my heart. I think

people only recognize us during Black History Month. They ignore us every other

day.”

There’s a reason

for that. He said, “There is a complete ignorance of what role African

Americans play in this country. When they talk about African American history,

they think it’s just African American history when it’s American history. They

don’t think it pertains to them when it’s America’s story.”

He hopes the

commemoration ceremony and the information shared will change that. But he

knows it will be a struggle. After all, 400 years have passed, but the lies

still persist about who the first Africans were, where they landed and what

they did.

But Brown knows

the truth and each morning when he comes to work, he sees that history. His

office is two-hundred yards from where they landed in Point Comfort, today’s

Port Monroe. And he has learned of their journey.

African Landing Day Commemoration

After the Portuguese

hired headhunters to attack Angola, 350 Africans were stripped of their

belongings, beaten and bound and packed inside the San Juan Batista in

1619.

The ship was

heading to Mexico when two English corsairs, hoping to find gold, attacked the Spanish

galleon-type sailing ship. Instead they found the Africans and took 60 to cover

their loss. These Africans had wondered at their fate as they watched more than

a third of their fellow Angolans, some they likely knew, die from sickness

while a few were sold for medicine. But these 60 were strong and among the

healthiest. And so, they were picked by the captains of the White Lion

and the Treasurer.

But the ships encountered

a severe storm and were separated, the White Lion was the first to

arrive at Point Comfort where more than 20, believed to be between 8 and 25

years old, were sold for food. The date was Aug. 25. The other ship arrived

days later. In a new world, the Africans adapted. They ended up saving the

colony and its settlers. The English settlers didn’t know how to farm and had

been relying on the Native Americans.

But when a war

broke out between them, many of the settlers were killed while others starved

to death – some resorting to cannibalism to survive.

This first

generation of enslaved Africans brought to Virginia were skilled farmers,

herders, blacksmiths, and artisans. They were accomplished traders. They also

brought many ideas and innovations including food production and crop

cultivation.

Because of them

the remaining English settlers survived. K. I. Knight, author of Unveiled:

The Twenty & Odd, said, “it was a stroke of luck for America that they

arrived. I don’t believe

America would have existed, certainly Virginia wouldn’t have been a colony,”

Knight said.

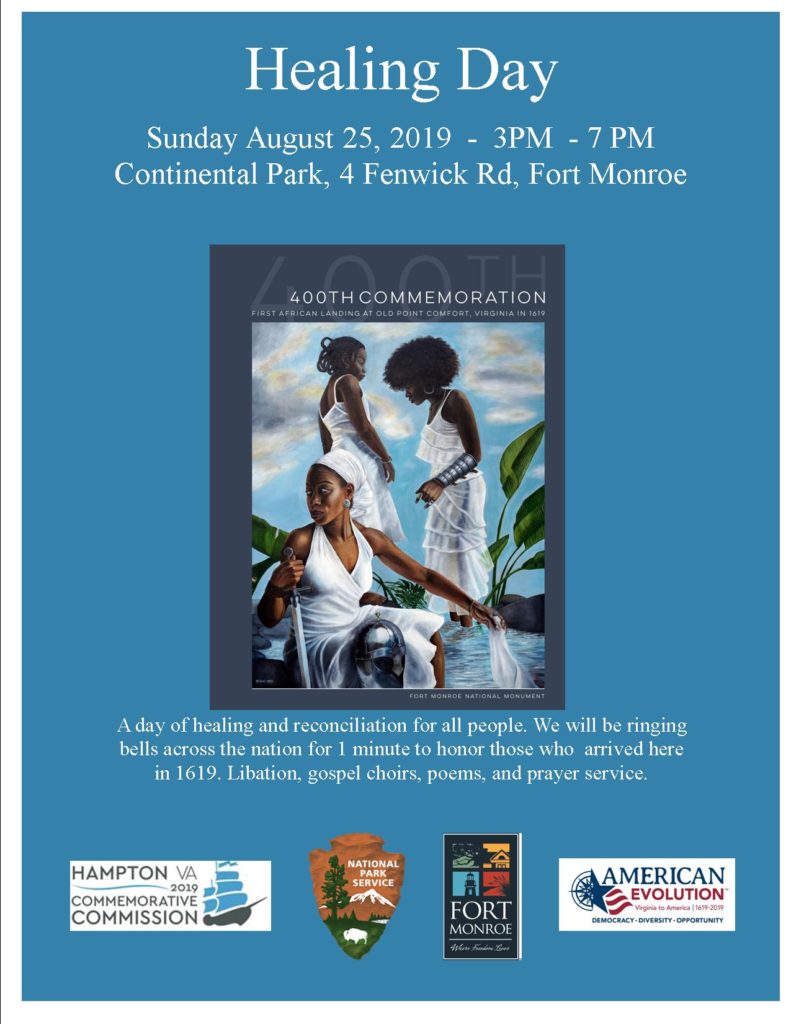

On Aug. 24, many will come together to

commemorate the day the first Africans landed with cultural demonstrations, vendors,

children’s activities, and more. Black Cultural Tours will be also be offered

from 12 to 4 p.m.

The day’s lineup will also include

dignitaries from Africa including the tribal king from Cameroon and people sent

by the president of Ghana, the KanKouran West African Dance group will perform

and an African Naming Ceremony will be conducted. There will be a procession to

the fishing pier for the flower petal throwing ceremony where they will throw

petals on the water to represent the lives lost during slavery, and at the end

there will be free concert at the Hampton Coliseum featuring the Sounds of

Blackness.

The program will

begin at 6:30 a.m. with a spiritual cleansing at Buckroe Beach before moving to

Continental Park. At 9:30 a.m. there will be a dedication of the Fort Monroe

Visitor and Education Center. The new visitor center will tell the story of the

first Africans. And the next day will be the Healing Day

Ceremony.

It will be a day of healing and reconciliation for everyone,

said Calvin Pearson, founder and president of Project 1619, which was formed to

tell the story of the first Africans. His organization helped to plan many of

the events.

“It’s not just

for Africans, but also for those who enslaved and oppressed us,” said Pearson whose

organization helped to plan many of the events.

Healing Day Ceremony

Though they were enslaved, they were

not considered slaves and were sometimes referred to as servants. But there

were still wide disparities between them and the white indentured servants.

The white indentured servants were

still legal subjects of the English crown and entitled to certain protections

including a contract that ensured their freedom after seven years. But the

Africans were different. They were aliens. They had to work 15 to 20 years to

get their freedom – and this was often at the discretion of the plantation

owners. Still, some fought in the courts for their freedom and that of their

families.

In the end, most, if not all, gained

their freedom. Some intermarried while others escaped with white indentured

servants.

But gradually the laws changed. “They

became early America’s indispensable working class—fit for maximum

exploitation, capable of only minimal resistance,” Ta-Nehisi Coates said in his

article, A Case for Reparation.

In 1661, chattel slave

labor law began and over the next 200 years the laws ensured that they remained

nothing more than commodities. Black

people were reduced to a class of “untouchables” while all whites were raised

to a level of citizens, Coates said. Intermarriage became illegal, everyone

except Blacks could carry weapons and once again the Africans were stripped of

all property and belongings. And on their backs and with their blood a nation

was built.

“Africans’ free labor built America,”

Pearson said. He said they built roadways, churches, schools and communities.

They built the memorials and monuments that America treasures as part of its

history. “Every major city and historical building built between 1619 and 1865

were built by Africans free labor,” he said.

Still,

recognizing and honoring this truth means little to many, Brown said. “Many

don’t believe their history is relevant. And so, he said, the unawareness is

pervasive. People just don’t know. That’s a black and white thing. People just

don’t know 400 years is here.”

To honor those

years, the commemoration will also include a National Bell Ringing Ceremony in

which churches and communities around the nation are invited to ring their

bells for four minutes, beginning at 3 p.m. on Aug. 25. On that day, there will

also be songs by gospel choirs, poetry, a prayer service as well as a libation

ceremony.

Still for Brown, who moved from

Boston to Virginia in 2016 to take the superintendent position, there was a far

more thrilling experience awaiting him. He attended an event soon after he

arrived and some people he didn’t know had joined him to take a picture. He was

curious to know who they were and awed when he found out. They were the

descendants of two of the first Africans to land in Virginia.

“That blew my mind,” Brown said. And

there were many of them, he said. Some of them will participate in the

commemoration honoring their ancestors whose courage laid the foundation for an

entire race of people in a new land.

Black History5 years ago

Black History5 years ago

Black History6 years ago

Black History6 years ago

Black History4 years ago

Black History4 years ago

Black History5 years ago

Black History5 years ago

Black History5 years ago

Black History5 years ago

Black History6 years ago

Black History6 years ago

Black History9 years ago

Black History9 years ago

Black History5 years ago

Black History5 years ago