Historians and political scientists are turning to the past

to frame the discussion about the more than 50 million Americans who have

already voted before Election Day, many of whom have stood in line for hours.

Media outlets are comparing an obviously energized electorate to the percentage

of voters who participated in the elections after the Civil War, but at least

one political scientist, Dr.

Sekou Franklin of Middle Tennessee State, hesitates to compare the percentages

of voter turnout.

“It’s much easier to make that conclusion if the voter

eligible population is very narrow and much smaller,” says Franklin. “So, I’m

very reluctant to do century-to-century or regional comparisons when the number

of eligible voters was much narrower than today.”

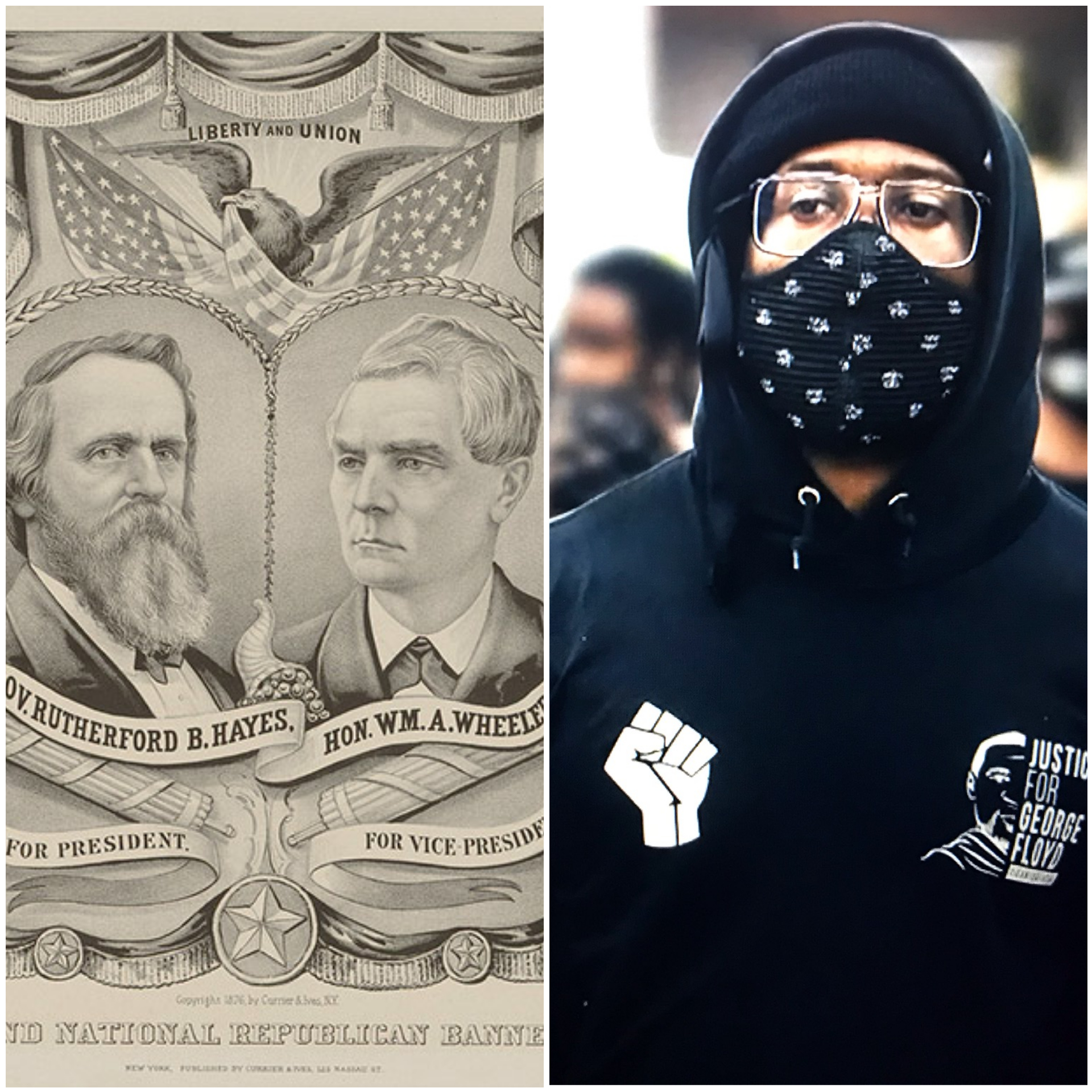

According to USA

Today, the nation “saw the highest eligible voter turnout rate, 82.6%, in

1876, when Republican Rutherford Hayes defeated Democrat Samuel Tilden. In

1860, when Abraham Lincoln defeated John Breckinridge, John Bell and Stephen

Douglas, 81.8% of eligible voters turned out.”

And voter turnout climbed above 80% in at least four other

elections in the 1800s.

Why So High

With the

passage of the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments, newly freed slaves embraced

their right to vote. Before the passage of the Amendment in 1869 granting Black

men the right to vote, voting rights advocates questioned the logic behind

disenfranchisement and pushed for the inclusion of Black men.

Delegates

attending the 1864 National Convention of Colored Men in Syracuse, New York

asked, “Are we good enough to use bullets, and not good enough to use ballots?”

Abolitionist Frederick Douglass attended the Convention and

said, “We are here to promote the freedom, progress, elevation, and perfect

enfranchisement, of the entire colored people of the United States; to show

that, though slaves, we are not contented slaves, but that, like all other

progressive races of men, we are resolved to advance in the scale of knowledge

, worth, and civilization, and claim our rights as men among men.”

And there was Congressional assistance in the effort. In

1867, Republicans in Congress passed a series of Reconstruction Acts,

overriding President Johnson’s veto. The first act required former Confederate

states to form new governments that enfranchised all “male citizens…twenty-one

years old and upward, of whatever race, color, or previous condition” before

they could be readmitted to the Union.

The next election saw Black men finally allowed to

participate at the polls which explains, in part, the high turnout numbers in 1868,

1872, and 1876.

Franklin points to the impact of what some historians call

“the squeeze” or in his words, “white voters in the South who were still

committed to the Confederate Cause.”

And he describes the 1876 election as “full of fraud and

voter intimidation, particularly talking about African American voters.”

It was the 1877

Compromise when newly elected Republican President Hayes struck a deal to

clinch the White House which included removing federal troops from southern states

that ushered in the end of Reconstruction.

More than a century after that fateful 1876 election,

Franklin cites the issues of today as offering the most striking historical

parallels.

“Those were elections in which race and federalism were at

the front and center,” he says. “And so I think, if you were to look at the

election today and what may be animating in the electorate, on the one hand,

you have Black and Latinx voters, perhaps…at least Black voters, some

Latinx…and still a pretty dogmatic, white racial grievance that’s gravitated

towards Trump. That those things are animated in that election as they were

animating in the election in the late 19th century.”

Black History5 years ago

Black History5 years ago

Black History6 years ago

Black History6 years ago

Black History4 years ago

Black History4 years ago

Black History5 years ago

Black History5 years ago

Black History5 years ago

Black History5 years ago

Black History6 years ago

Black History6 years ago

Black History9 years ago

Black History9 years ago

Black History5 years ago

Black History5 years ago