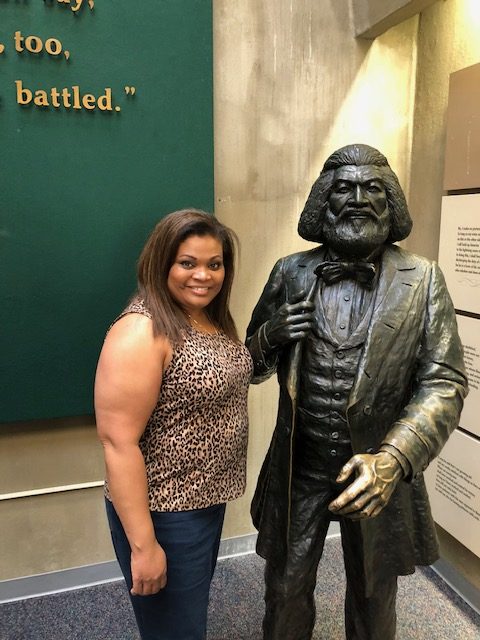

Tara Buckner visited

the Washington, D.C. home of abolitionist and orator Frederick

Douglass during a business trip to the nation’s capital in 2018. She

still remembers the elegant wallpaper, the curated collection of family heirlooms,

and the china.

“I believe he

brought it back from the islands,” she said. “And, they have it all

set up in the pantry.”

Douglass moved into

the house which he called Cedar Hill in 1877.

In 1922 it was declared a National Shrine, and the federal government

recognized the hilltop home in the Anacostia neighborhood as a National

Historic Site in 1988.

During a library reading, biographer

David Blight, who won a Pulitzer for Frederick Douglass: Prophet of

Freedom, shared with the audience the historical context for Douglass’

commitment to living in Washington. Blight recalled that it was the winter of

1866 and Republicans had appointed a committee to study Reconstruction,

seeking ways to stabilize the formerly enslaved and ensure access to

opportunity.

“In the midst of

those hearings, Douglass is in Washington,” Blight said. “He didn’t

live here yet. He’s

not going to live here until 1872…although right at the end of the war he was

trying to get to Washington, he was trying to get to the center…he was trying

to get somewhere near or inside Republican politics if he could.”

According

to Blight, Douglass — an admired statesman — led a delegation of 12 other

Black leaders to the White House to see President Andrew Johnson. They did not

have an appointment but asked for one which Johnson granted. However, Johnson

was not “terribly welcoming.”

Blight

stated, “But what ensued that

day was probably one of the worst encounters between a group of Black leaders

and an American President ever, in our history.

It was a disaster one might say.”But, Douglass was not dissuaded. When Rutherford Hayes was elected, Douglass became the marshall of the District of Columbia. It marked the first time a Black man successfully received a federal appointment requiring Senate approval.

Douglass’ ability to

overcome a lifetime of discrimination is why Buckner felt compelled to visit

the home which Douglass had purchased for $6,000.

She remarked,

“His experience coming out of having been separated from his mother at a

young age, being flogged, sneaking to learn to read and write speak to the very

existence of the terrible life of slaves.”

With the growing

popularity of Juneteenth, Douglass’ famous speech in 1852

questioning the relevance of the Fourth of July to the enslaved has received

renewed interest. Yet, for Buckner, whose daughter was born on the holiday, the

Fourth now has added meaning.

“I feel as a

descendant of slaves…every day is a question so for me to have my baby on the

Fourth solidifies my story as an American in this country,” she explained.

But despite what

Douglass queried in his speech, Buckner in 2020 can claim the Fourth of July

and “rejoice” along with many others, in part, because of his

“extraordinary” accomplishments and sacrifices often first envisioned

at the quiet respite he called home.

Black History5 years ago

Black History5 years ago

Black History6 years ago

Black History6 years ago

Black History4 years ago

Black History4 years ago

Black History5 years ago

Black History5 years ago

Black History5 years ago

Black History5 years ago

Black History6 years ago

Black History6 years ago

Black History9 years ago

Black History9 years ago

Black History5 years ago

Black History5 years ago