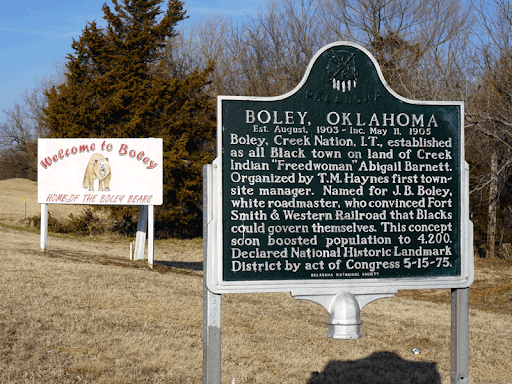

During the decades when Black people were being suppressed and subjugated by racist laws, many fought to carve out their own place in a segregated society. The results were black-owned businesses, churches and clubs. Some led the way to establish their own neighborhoods, organizations and newspapers. They built their own banks, schools and parks. And these became legacies of their fight and their success. But many of these legacies have been neglected and forgotten. For Black History Month, TheVillageCelebration will look at some of these abandoned legacies.

Henrietta

Holloway Hicks can still remember the stories her family told her about Boley.

When her uncles, who looked white, were chased out of their Black Louisianna neighborhood

for being friendly with white girls, the family sought refuge in the small Oklahoma

town.

They became

one of the original settlers of the predominantly Black town that would soon see

a population numbered in the thousands and become known by many for its

prosperity.

It was the

early 1900s and the Fort Smith & Western Railroad was still using steam

engines that had to be filled with water for at least every six miles. It made

a stop in Oklahoma. And two men, one a manager for the railroad, saw a few

black families living in the area.

At that

time, “There were shotgun houses and dugouts, log cabins people threw up just

to have a place to live in,” said Hicks, who at 85 is considered the town’s

historian.

The men

decided to build a town and Boley

was officially opened for settlement in 1903 in Creek Nation, Indian

Territory. The group that founded Boley: Lake Moore, a white attorney;

John Boley, the white manager for the railroad; and Thomas M. Haynes, a black

farmer and entrepreneur from Texas, began by buying property from a child.

With the help of

James Barnett, a Creek Freedman, they purchased the land of Barnett’s 12-year-old

daughter, Abigail, to establish Boley’s base, Hicks said. At that time,

Native Americans had slaves who, after they were freed, were given land, Hicks

said.

The men then reached

out to Black people who came from all over, Hicks said.

“They

brought in this man, planted the town and invited other Blacks who were running

away from segregation. They came by the droves. They came by the carload. They

came by the train-load.”

If You

Build It…

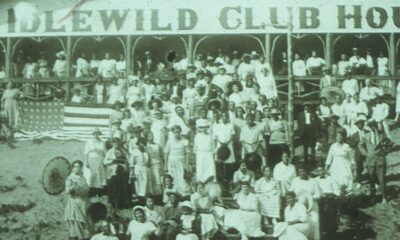

Many in search of freedom

and better opportunities flocked to Boley and the town grew to become the

largest predominantly black town in the United States. During the early part of the 20th century, it was one of the

wealthiest Black towns in the nation, according to online reports.

It boasted two banks,

including the first nationally chartered bank owned by Blacks, three cotton

gins and its own electric company and water system.

It had people of all professions including seven physicians

and a hospital, three dentists, lawyers and architects, Hicks said. It had a

car dealership; grocery stores; hotels; restaurants; nightclubs; churches and

fraternal clubs. Its Masonic Lodge was reportedly called “the tallest

building between Okmulgee and Oklahoma City,” before it was destroyed by an arsonist.

Boley had a railroad depot, a post

office, a telephone company, and a power plant. It had a black

tuberculosis hospital and the State Training School for Negro Boys. All

who visited Boley, including Booker T. Washington, marveled at the ambition and

vigor of the townspeople, according to Blackpast.org.

By 1911, the town had more than 4,000

residents, and was home to two colleges: Creek-Seminole College, and Methodist

Episcopal College, according to online reports.

“Our schools were equal to none,” Hicks

said. When her mother went to school, she said, “they used to teach Latin. They

taught everything they thought Black people needed to learn.”

The schools were so well known that at

least five yellow buses would bring in students daily from the outlying areas

to attend the schools.

“We had our own schools. We had our own

everything. But when integration came, it changed things,” Hicks said. “People

just migrated and left.”

After Oklahoma’s statehood in 1907, the

citizens of Boley, like all Blacks in Oklahoma, struggled for their civil

rights.

“Although the day to day effects of

segregation were muted in Boley, most people in the town were disfranchised in

1910 when the grandfather clause became law,” according to Blackpast.org. “However,

Boley was an important location for all Blacks in the state as they worked to

fight disfranchisement for the next two decades.”

In addition to political turmoil, the

town also faced financial problems that plagued most small towns in the United

States at the time.

After World War I, a fall in agricultural prices and the

bankruptcy of the railroad helped lead to Boley’s failure. And it went bankrupt

in 1939 during the Great Depression.

Before World War II, Boley’s population had declined to about

700. And by 1960 most of the population had left for other urban areas.

The younger generations, after finishing school, left to find

work, said Hicks, who also left when she was in her 20s before returning almost

two decades later. Many of the farmers also left after the boll weevil began destroying

their cotton, she said.

“Then, of course, the government came along, saying you can only

grow a certain amount of acres of cotton,” Hicks said. That caused more people

to leave, she said.

Now there are about 500 residents left in

the town and about 800 to 900 inmates in the state’s minimum-security prison

that’s housed in the building that was once used for training incorrigible Black

boys, Hicks said.

Many of the buildings are old and have

been left abandoned in the small town by citizens who never returned, Hicks

said. Still, life in the town saunters on and Boley remains one of the state’s few remaining historic African American

towns. At one point the state of Oklahoma had about forty Black towns, Hicks

said. Now, she said, there are about thirteen and all of them have only a

handful of residents or more.

Boley,

home to many descendants of the town’s original settlers, still has the largest population. It still has a fire chief, a police chief and four reserve officers as

well as a judge, a mayor and its trustees. The post office is also still there.

Often, tourists come to visit the town

and a rodeo every Memorial Day weekend brings in thousands to the community.

“Boley was a very prosperous town, but

times bring about change,” Hicks said. Still, she wants people to know the

history of the town and its worth.

“People feel like

there is a bit of freedom when they come here,” Hicks said.

Black History5 years ago

Black History5 years ago

Black History6 years ago

Black History6 years ago

Black History4 years ago

Black History4 years ago

Black History5 years ago

Black History5 years ago

Black History6 years ago

Black History6 years ago

Black History9 years ago

Black History9 years ago

Black History5 years ago

Black History5 years ago

Black History6 years ago

Black History6 years ago